The Holy Grail or a missed opportunity?

For many years now I have read about the desire to be able to demonstrate value for money in corporate training and development. Type ROI for training into any search engine and you can find hundreds, if not thousands of educated opinions on the subject.

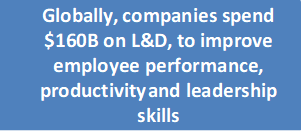

There are justifiable reasons why a business owner or senior executive might want to know what they are getting for their money, particularly when you can find statistics associated with the ROI searches such as these:

And yet despite these depressing statistics, according to Deloitte Human Capital in a report in 2016, 84% of senior leaders believed leadership and development investment is vital for the success of their organisations.

So, off the back of the fact that of $160 B spent almost $120 B is ineffective and that 84% of leaders still believe that investment in L&D is vital, I make no excuse for now publishing my own thoughts among the thousands already out there.

What I would like to offer however is my thoughts on why we measure on not just what we measure. I will then offer some alternative ideas on what we can do to ensure the information we gather from a fresh approach to measurement can help influence how we support our learners to become the best they possibly can.

If you take a look at both of my web sites https://www.salesimprovementservices.com/ and http://tpacoaching.co.uk you will see that I have long been an advocate of the benefit of measuring training and development and I have further advocated we do so on the basis of organisational impact.

This is only fair, as the organisation is investing in its people and has a vested interest in their team members specific development which should be aligned to organisational objectives.

A private company will be responsible to its shareholders and a not for profit or government agency will be responsible for maximizing the efficiency of funds made available for its cause.

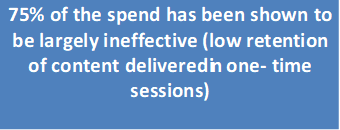

The intervention measurement is generally made against four potential categories for impact:

• Quantity; How many, more or less

• Quality; How much better

• Cost; How much, more or less

• Time; How much, longer or shorter = increased margins.

I visualize this as such an input, change and output process:

This process should be supported by training and coaching interventions to help embed the development and change required.

These are reasonable expectations for any organisation to expect from an investment in training. Expressed in a classic input, output diagram we can start to measure contribution improvements against at least one of the key categories. If we measure these against SMART objectives and against a curriculum or intervention, an organisation might be able to gather enough data to at least justify the spend.

My question however is what are we missing by restricting the measurement purely to output?

What other benefits might an organisation want to acquire from investing in its workforce?

What else should we consider if such measurements are to provide us with better data to help improve the ROI and to address the rather depressing estimate that 75% of spend is ineffective?

Let’s consider the human element of development.

The human element around training and development is of course central to the conundrum, if we do not employ people, we do not need training. But if we do, then we surely have a need to develop our workforce if we want our organisations to thrive.

84% of leaders still believe this is vital.

I will consider the human aspect of this challenge from two perspectives, firstly the organisations people strategy and then from the perspective of the employee or learner. Both have an important influence on what we might need to measure.

Before I get into these two aspects, I would like to share some thoughts on measurement from Bernard Marr, author of several books on big data, using key performance indicators and on measurement. In his book Managing and Delivering Performance, Marr outlined why we measure and suggests that we measure for three reasons:

- Because we don’t trust people to be able to carry out their functions.

- Because we must; due to compliance drivers.

- To provide feedback to help develop learning and empowerment.

It is the latter where we should focus our attention if we want to support our team toward organisational and personal development. It is from the latter I also base my opinion around.

The use of data derived from measurement and provided as feedback should extend to support the employee not just in their current roles, but also their future roles within your organisation and perhaps beyond. Providing feedback to help the learner develop is fundamental in the success of an organisational people strategy and for individual development.

From the business perspective

This about how the organisation has developed its people strategy there are several elements to consider. A full review of the PESTLE environment might influence your HR policy to address things such as:

- What is the political situation of the region where you operate and how can it affect the recruitment and retention of staff?

- What are the prevalent economic factors, is it an employer’s market or an employee’s market and how does this effect salary structures?

- How much importance does culture have in the region and what are its determinants?

- What technological innovations are likely to pop up and affect the development needs of the team?

- Are there any current legislations that regulate the industry or region, or can there be any change in the legislations that might affect you?

- What are the environmental concerns for the organisation, can a people focused strategy change negative perceptions of your industry or your organisation?

Other specific things to accommodate might include:

Raising employee productivity: Increase staff loyalty to the company; Develop more flexible employees; Improve staff morale; Develop core skills; Improve quality of company products/ services; Improve company image; Change behaviours or culture.

Our measurement should include how the organisation and its learning and development philosophy is shaped from the data collected.

A Case study.

In a recent coaching intervention, I have been supporting a senior manager in a global B2C organisation. The organisation has purposely implemented a strategy in my client’s local region to recruit new graduates with less experience and who might demand less salary than a more experienced person. This strategy helps the organisation to differentiate an employee offering that might look attractive to someone new into the workplace. With an international reputation for developing its people and benefiting from size and longevity, it can offer graduates secure employment, an excellent development path into more senior management and variety in terms of functions and career progression.

Off set against this is an employee’s market place where quite often smaller firms are paying as much as 20% more for similar roles. The attraction of a quality development programme and an opportunity to gain a broader experience can sound attractive to a new graduate into the work environment.

Measurement of success is not purely on output, although this is still important, but includes staff retention levels, employee satisfaction, accreditation and effective internal recruitment numbers versus recruiting from outside of the company.

Our coaching work has been around helping the senior leader consider methods of retention and interventions to ensure the team stay engaged and motivated and retain their enthusiasm for further development.

The intervention has helped the organisation engage effectively with millennial’s in their region and help maintain their international reputation as an attractive employer to work for.

For my coachee, measurement of purely output would have missed some important, none direct business drivers that have been able to influence an overall approach to people management.

With Generation X now becoming the majority of the workforce and with Generation Z entering employment for the first time, it is important to consider how an organisation might need to alter how it measures success and how it might support staff that are operating in what is termed as a VUCA world, (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous).

An interesting statistic from Gallup in 2018 stated that “87% of millennials are seeking professional development more than any other benefit”. How can an organisation use this statistic to help promote and advance its training and development offering?

Changes in culture, values and world events provide suitable reasons why an organisation might want to measure success differently and this will in turn help the organisations forge enhanced and more appropriate development programmes to support their employees.

And what about the employees themselves?

From the employee perspective

According to Bain & Co, one of the world’s leading management consulting firms: “most leadership development programs aren’t up to the job of working with individuals on capabilities that many feel are nebulous, overly personal or hard to assess. More inspirational skills are exactly what today’s environment requires.”

A one size fits all approach is essentially a cop out.

Traditional training methods often rely heavily on a single ‘expert’ disseminating information. This can be problematic as many training courses are heavily didactic – the information contained in an ‘off the shelf’ adult learning package might not be applicable to everyone in their real-world employment. Once the session is over and the expert has gone, there is nobody to whom questions can be directed and the learning exists entirely in a temporary bubble.

Researchers looking at productivity, leadership and development have made an interesting discovery which supports social learning theory and brings into question previous training methodologies. Anyone who has begun working for a new company will know that after the initial induction period, most ‘on the job’ knowledge is gained from asking colleagues and those around you.

Research has shown that regardless of what position you’re taking in a company, you will learn around 10% from formal training in your induction and the remaining 90% via your direct experience and expertise shared by colleagues. The 70:20:10 model was developed across the 1980s and 1990s by Morgan McCall.

The model splits our understanding of the learning process into three separate sections, noting that 70% of our learning comes from our direct experiences, 20% comes from our social interactions with others and the remaining 10% comes from formal training.

Management development teams are beginning to understand the powerful combination of the 70:20:10 model. Traditional training methods may have had their day. Our brains have been bolstered by ever more sophisticated technology, and this combination is creating a new, innovative and exciting world for adult learning across the globe.

This is even more evidence to suggest we need to take a fresh approach to training and development methods and therefore an alternative approach to how we measure the value of such interventions too.

I would like to consider for a moment the motivation factor and how this might affect training and development and its measurement. If an employee is not motivated to learn, the intervention will be less successful than if the learner was fully on board. A disinterested learner will have a negative effect if we just measure the intervention against output or organisational objectives.

Impact can be measured on output but the need of the learner and the preference for them to take ownership of their own development is also an important factor to consider. Without motivation and drive from the learner, and only data collected on output, we may decide to amend what was a good intervention due to the wrong reason and floored feedback.

An analogy.

I recently took part in a development programme that was based on the thoughts and theories of Fred Kofman, from his book Conscious Business. During his introduction to the programme he suggested that the greatest impact of a training programme might come from the decision to have enrolled on the programme in the first place.

As an analogy, he shared a story of how a group of researches decided to review the benefit of patient participation in shorter term therapy compared to a more traditional long-term psychoanalysis intervention.

He mentioned how they had tried to measure impact of long-term support against a short-term programme consisting of 8 session. The analysts discovered that 90% of the benefit for the patient had been derived sometime within the shorter term 8 session intervention which impacted just as much as the longer-term intervention.

They then decided to extend the research and investigate the impact over four sessions (halving the intervention duration), amazingly they discovered that 90% of the patient benefit had been derived from the first four sessions. They then took the analysis down to 2 sessions and eventually one session and, once again they found that 90% of the benefit had already been achieved after one session. Being analysts, they could not help but review what might happen with no therapy and they found that again 90% had been gained prior to the formal therapy being started. The conclusion was made that perhaps the greatest impact a patient gains from a therapeutic intervention is gained from their decision to enter therapy in the first place.

I have experienced a similar scenario when a few years ago I gave up smoking. The biggest impact I believe was my genuine desire to quit and was only supported by things such as nicotine patches and e- cigarettes. The biggest shift and the reason for my success of quitting came from my desire to quit rather than the methods I used to sustain my abstinence.

I wonder if the same is true for many development interventions? If so, we might benefit from altering our measurement. At the very least we should include a more rounded approach to measuring intervention that takes into consideration the state of mind and motivation when a learner embarks on a programme of development.

Another interesting theory was shared recently in a response to a training query I read on measuring return on investment for coaching.

John Parker, Director of The Academy of Leadership and Management wrote” My first degree was in Chemistry and I rarely used it, other than to draw scientific thinking and metaphors. Here is a metaphor for you. Coaching, and to a lesser extent, other interventions, are catalytic in nature. A catalyst can be defined as an agent added to a system that speeds up the reaction time or improves the conditions without changing itself. Looked at like that, and especially if you can spot the point at which the catalyst has acted, and you can say that, without the intervention, this would not have happened. That is a statement that is almost as powerful as this intervention caused this outcome and demonstrates its value.

Whilst John used this analogy to provide some interesting feedback around measuring impact of coaching interventions, this does have a parallel to the effect on most training and development interventions. What was the catalyst that stimulated the change in behaviour? How can we identify this and how do we measure it?

We are in danger of spending a lot of time, effort and money on measuring the wrong things.

Referring to Fred Kofman again and my recent development programme, whilst I listened to the introduction to his training intervention, he suggested that teaching is pointless. He suggested he could teach the participants very little, all he could do as a trainer was facilitate the participants own learning. It was up to me (and the other participants) to establish how we might learn and how we might then use the information that we had shared from our session.

This would indicate that for training and development to be effective it needs to be taken by people that have already made the decision that they have a gap, being a position from where they are, to where they want to be. They should already have committed mentally to find information and methods to help them bridge the gap.

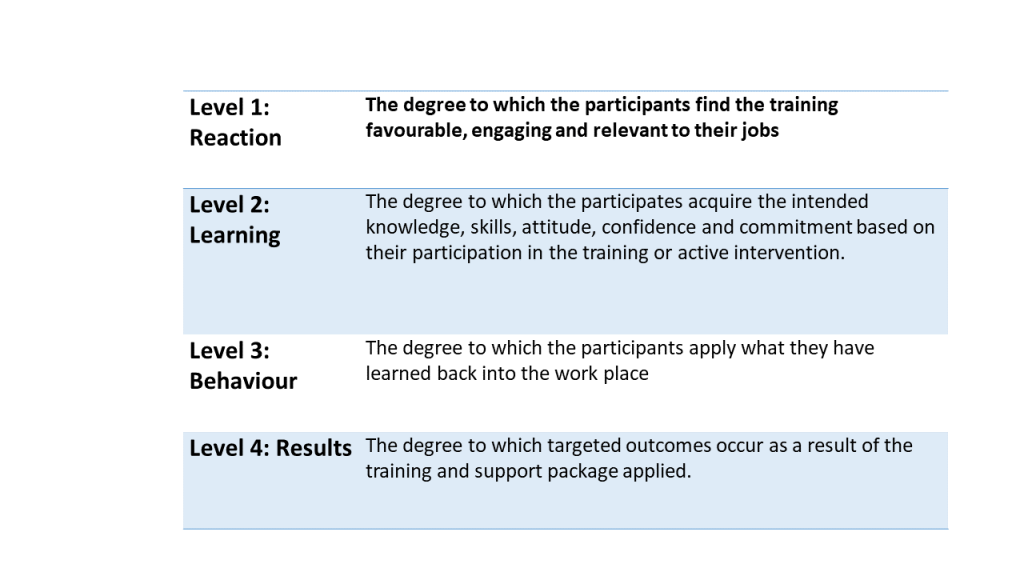

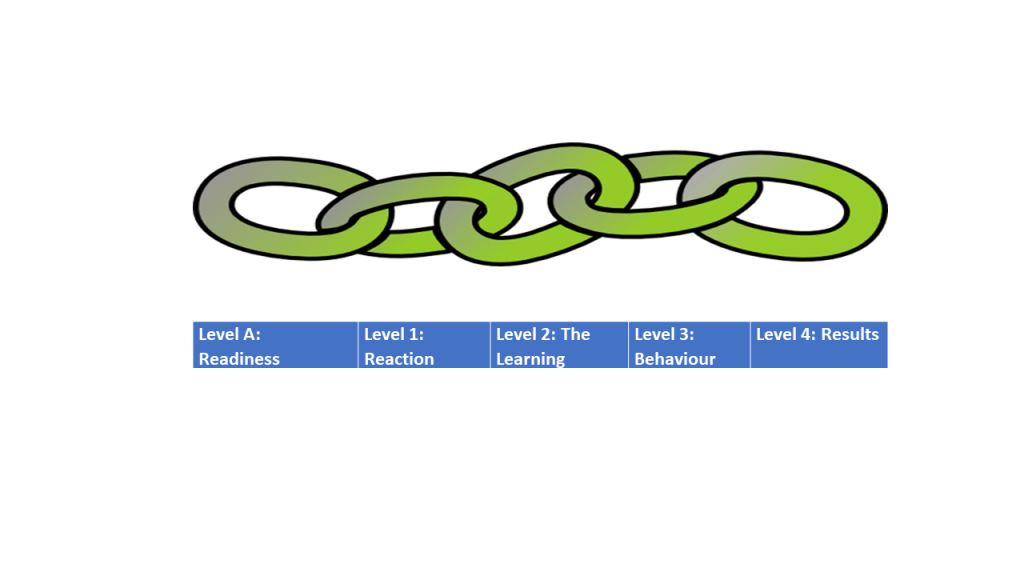

I like to include the Kirkpatrick model in my own assessments. This is of significance because it asks four key questions to determine if the intervention has been successful and considers the learners journey as well as the organisational requirements. It measures the following:

To accommodate the mental readiness, I referred to earlier we might add a link to the chain from the Kirkpatrick model that includes some pre-assessment around the learner’s desire to change as follows:

I believe this five-phase approach to measurement would add depth and quality to the organisational drivers of Quantity, Quality, Cost & Time.

It will help us to share great evidence with senior stakeholders on value for money for the individual, the organisation and the effectiveness of the processes being used to accommodate and support the training and development.

It can help us measure training and development with greater depth and clarity.

In Conclusion

Fred Kofman described the Three Dimensions of Business in his book Conscious Business. He suggests that every organisation has three dimensions: the impersonal, the task or the It; It has an interpersonal element which includes the relationship or the WE and finally it has the personal element, the self or the I. This is a fascinating concept and one I strongly recommend you research but considering the IT, WE and I in terms of measuring the effectiveness of training and development we can apply this to measuring:

The IT = The process or method of delivery.

The WE= The benefit to the learner, the organisation and the wider stakeholders

The I= the skills, ability and the desire of the individual to take ownership of their own learning journey.

I think it is time we reassessed how we measure the ROI for training and development so we can take a wider and deeper review of the effectiveness of the investment and hopefully move the 75% failure rate to one that delivers greater satisfaction to the organisation and the learner.

We need to consider measurement and use of the data collected to review the learner, the organisational benefits and the development process.

In my next article I will share some thoughts on how coaching can add value to all developmental programmes.

I would be interested to learn of your perspectives to this article. All comments are gratefully received.